VisAbility kicked off its project “Making Ability Visible” in the district of Anuradhapura between 2 and 15 July 2015. We stood in Talawa, at the facilities of our local partner “Association of Women with Disabilities” (Aabadha Sahitha Kanthawange Sangamaya, AKASA), which trains women with disabilities to manage daily life by themselves. Therefore, we had the opportunity to socialize with local people with and without disabilities, including future participants of our workshops and their parents.

During our time in Talawa, we had the following aims: firstly, to research the local situation, gain a better understanding of the challenges and opportunities for people with disabilities, and produce a report. Secondly, to meet with local and national governmental representatives for the presentation of our work on the protection of people with disabilities by the Sri Lankan government and its services. And thirdly, to execute our workshops on mixed-abled dance and disability rights.

“Forget about disabilities”

Before and after the workshops, Helena-Ulrike Marambio and Nirma Karunarathna (translator and legal advisor), interviewed some participants with disabilities and their relatives at the facilities of AKASA and their homes. The results demonstrated that the majority of people with disabilities and their parents had experienced some kind of rejection at school and/or within the village. Consequently, some youngsters with disabilities showed a lack of trust towards strangers as they feared to be categorized as ´dump` again, as well as poor self-confidence regarding an independent life in the future.

However, interviewees also provided inspiring examples of support: Hashan, a young man in a wheelchair, stated that friends accompanied him to school when he became a youngster. Previously, Hashan’s mother carried him to his seat in the classroom until the school administration pushed for the establishment of a ramp for him. Another example is that of a teacher who had encouraged a 7-year-old pupil, Dewmini, to attend his class for ´normal` pupils in addition to her ´special needs class` in order to stimulate her education.

Overall, parents demonstrated a strong will and stamina to support their child/children with disabilities, despite negative attitudes from, for instance, family members and neighbors. Unfortunately, such reactions remain quite common within Sri Lankan society. Rejection is based upon religious misbelief; it is assumed that people become disabled as a punishment for mistakes committed in previous lives. It is particularly difficult for pupils with disabilities at school, who face untrained teachers, and/or classmates’ parents who lack knowledge of the causes of disabilities. Employers, too, do not want to hire working-age adults with disabilities, as they do not see their actual capacity and willingness to learn. However, some of the parents we interviewed were able to change this perspective in favor of their child: “Neighbors said that it is useless to send Hashan to school”, explains Hashan’s mother, who always herself saw the importance of a solid education. Over time, her son proved to his neighbors that he had the necessary skills and abilities to make his way. Despite these struggles, people with disabilities are in high spirits. When we asked Hashan what advice he would share for people with disabilities in Sri Lanka, he immediately stated: “Forget about disabilities, let´s focus on the future.” According to him and Janaka, a 37-year-old man with a stiff leg due to an accident, people with disabilities should themselves become more aware of their potential and real abilities, and break with boundaries (established both by them and their environment) by speaking up and trying out new things in life. This is one of a diverse number of ways to change the perspective of society and turn challenges into opportunities.

Lack of support by the government

Despite such positive achievements, all families complain about lacking access to any kind of information on disability rights and other facilities for people with disabilities provided by the government (vocational training centers, special need schools, and financial support).

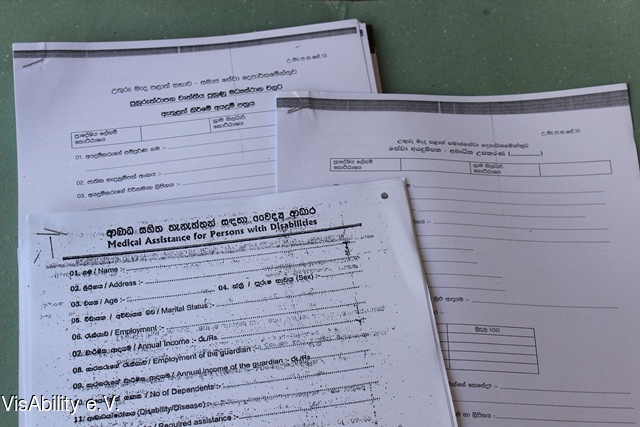

They also mention the difficulties that surround applying for an allowance (support for the set-up of self-employment, medical assistance, and monthly life aid) from the Social Welfare Ministry. Our research shows, for example, that applications for life aid of 3000 Rupees (approx. 20 Euro) are often rejected with the accompanying varying explanations given by the Divisional Secretariat officers being verbal, and mainly without legal grounding. In other instances, approvals have taken up to two years to come through, during which time parents have struggled to pay the necessary costs required to travel to the Divisional Secretariat to inquire into the process. Often, parents have received no clear answer at all. In what seems to be a common practice, parents and people with disabilities are given no update on the status of their application – even if officers know that it has already been rejected. Applicants are left in a kind of limbo and, as a result, most simply give up.

Meetings with the authorities

Addressing the above-mentioned problems, VisAbility took the opportunity to talk to the authorities on different levels to express its concern and its demands for the protection and support of people with disabilities in Sri Lanka. During the first meeting, we presented our pilot project “Making Ability Visible” to the Minister of Provincial Health, Indigenous Medicine, Social Welfare, Probation and Child Care, Environmental & Provincial Council Affairs, Honorable K.H. Nandasena, and the Additional Secretary of the Anuradhapura District Secretariat – Divisional Secretariat, E.G.U. Rajapaksha. We also requested help to obtain a permit from the police for our public performance in the center of Anuradhapura at the end of the mixed-abled dance workshop, as well as access to information on and about people with disabilities. Furthermore, we asked to put the rights of people with disabilities in the mainstream and to do everything possible to ensure equal opportunities and full participation as Sri Lankan citizens. The Minister and the Additional Secretary both promised to support our requests and project as far as possible.

Some days later, we met the National Coordinator of the Ministry of Social Welfare, Mr. Shantha Kumara. We expressed our deep concern regarding the various delayed replies and rejections of applications for allowances for people with disabilities, and the high administrative burden surrounding eligibility to apply. In addition, we asked why people with disabilities and their families do not receive any clear written statement on the procedure. On the latter, the Minister recognized this problem, but did not give any reasons. Mr. Kumara also admitted that the conditions to apply for allowances are more likely to be barriers for the applicant and family. However, according to him, the government is more focusing on the empowerment of people with disabilities rather than financial aid, in order to decrease dependence. In this context, VisAbility underlined the importance of individual case studies by officers with regard to people with disabilities to adequately reach sustainable development for and with people with disabilities. Not every person can simply be empowered by a short day’s program; some individuals may need further pre-conditions in place, such as school transport allowances to be able to receive solid education to enter into the labor market later on. Moreover, VisAbility stressed the need for stronger monitoring and communication among the diverse governmental divisions and districts. Mr. Kumara identified this issue as quite challenging among all regions. Finally, we were able to present a case of pupils with disabilities forced to leave the school due to discriminatory attitudes by a teacher and principal. The Minister expressed his concern, and asked that we send him a case report.

“It was the first dance experience where I was not pushed around”

VisAbility´s four-day workshop on mixed-abled dance started on 6 July 2015 with a group of 21 people with and without disabilities. It concluded with a public performance at the new bus station in Anuradhapura during the afternoon rush hour. In order to raise awareness, VisAbility and participants of the workshop distributed flyers in the market and the new bus station some days before.

Based on techniques of contact improvisation, people with and without disabilities gradually opened up and started to interrelate and communicate through dance about experienced situations and related emotions. Some of the participants with disabilities were very shy, almost afraid, due to previous bad experiences, to touch strangers. Eventually, however, they overcame their fears and appeared to be more self-confident. A 13-year-old deaf girl who wanted to leave the workshop after the first day, and tried to hide herself behind her mother most of the time, completely changed her behavior: on the second day, she actively sought contact with other participants and increasingly enjoyed her time. However, it was not only difficult for people with disabilities: Praba Jayasinghe, a dancer who is assisting the choreographers Gerda König and Mahesh Umagiliya, reflects: “I have never taught people with disabilities before. It was hard for me to find an entry point to both gain their trust and make me understand them. I had to overcome my own barriers.”

The choreographers Gerda and Mahesh asked the participants to overcome cultural and social boundaries through techniques of contact improvisation, especially those between people with and without disabilities. The biggest challenge for all workshop members was breaking with former ways of seeing ´other` bodies, and to develop a different perspective that uncovers the ability of each.

Moreover, Gerda and Mahesh encouraged the group’s active participation and to use any possible movements to contribute to the development of a mixed-abled dance piece. Although some of the participants had already taken part in performances, for most it was the first time they had worked in such a creative way, having previously followed instructions and remained passive. Chatu, a 28-year-old woman who is sitting in a wheelchair, highlighted: “It was the first dance experience where I was not pushed around”.

VisAbility came and did our work

During the disability rights workshop run by Helena and Nirma, participants learnt about international human rights and national rights for the protection of people with disabilities. They received advice on possible institutions to approach in case of severe discrimination and other violations of their rights. In addition, we presented different existing types of application forms for allowances, and explained obstacles relating, firstly, to how to fulfill all of the application criteria , and, secondly, to get the form processed and hopefully approved. The information offered was highly appreciated: based on a survey done before the start of the workshop, most of the participants were not aware of all possibilities they are entitled to. The workshop also trained participants to solve various challenging moments through role-plays. Finally, people were encouraged to create self-help and pressure groups to get their voices and demands heard.

After the end of the disability rights workshop, participants of the mixed-abled dance workshop presented the developed piece on the road in front of the facilities of AKASA. Vehicles had to stop. The Director of the Social Welfare Department also formed part of the audience. Before handing over certificates to all attending persons, he admitted in his speech that VisAbility came to provide services to the people on the ground which would have been the duty of the Social Welfare Ministry. For youngsters such as 13 year-old Kasunika, the reception was overwhelming. She proudly said: “This is my first certificate in my life!”